Leaving no one behind amid climate change in Asia and the Pacific

Over 4 in 5 people in Asia and the Pacific face multi-hazard risks associated with slow or sudden onset climate events. However, the degree of exposure is by no means uniform across individuals and households and diversity prevails in vulnerability to and capacity to cope with climate change.

Increased exposure to climate change events is associated with individual and household characteristics

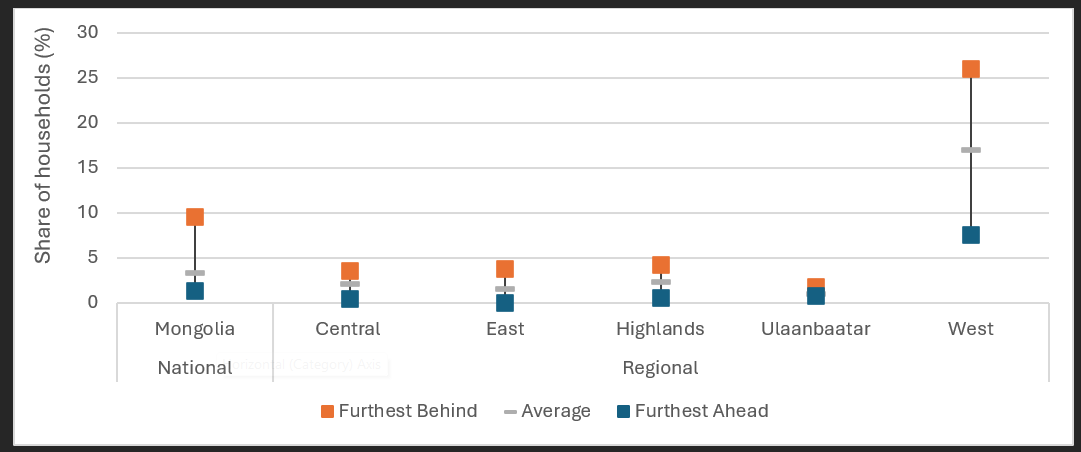

Where people live and why can influence the degree to which they are exposed to climate change. Poorer households living in rural areas are particularly at risk. Take the example of Mongolia (Figure 1). On average, 3.3 per cent of households experienced a climate change induced disaster in 2022. Across its five regions, prevalence and variation of exposure is relatively low except in Western Mongolia, where one in six households were exposed to disasters. Furthest behind are poorer households living in rural areas where more than one in four were exposed to a disaster.

Figure 1 Exposure to disasters in Mongolia

Note: Author’s elaborations based on ESCAP LNOB algorithm applied to Mongolia’s Household Socioeconomic Survey (2022).

Poorer households living in remote areas are affected also in small island developing states like the Maldives and Vanuatu. As shown in ESCAP’s latest Social Outlook, exposure to climate induced disasters was twice as high in remote and rural areas as in urban areas in Vanuatu. The gaps were more striking in the Maldives where households living in the capital were four times less likely to be affected by disasters than those living in other atolls.

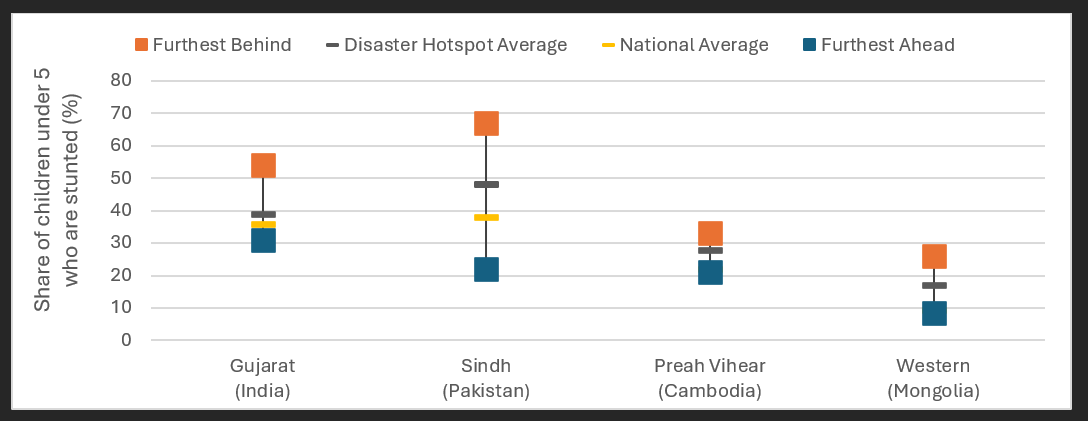

Climate change is also disproportionately affecting people already in vulnerable situations. Take the case of child malnutrition (Figure 2). There is higher prevalence and wider variation in stunting among children under five, in selected disaster hotspots across the region. In disaster hotspots, children living in larger and poorer households are often furthest behind.

Figure 2 Child malnutrition in disaster hotspots

Source: ESCAP LNOB Platform based on latest DHS and/or MICS data (2018-2022) accessible at https://lnob.unescap.org/.

Wide inequalities persist in coping capacity

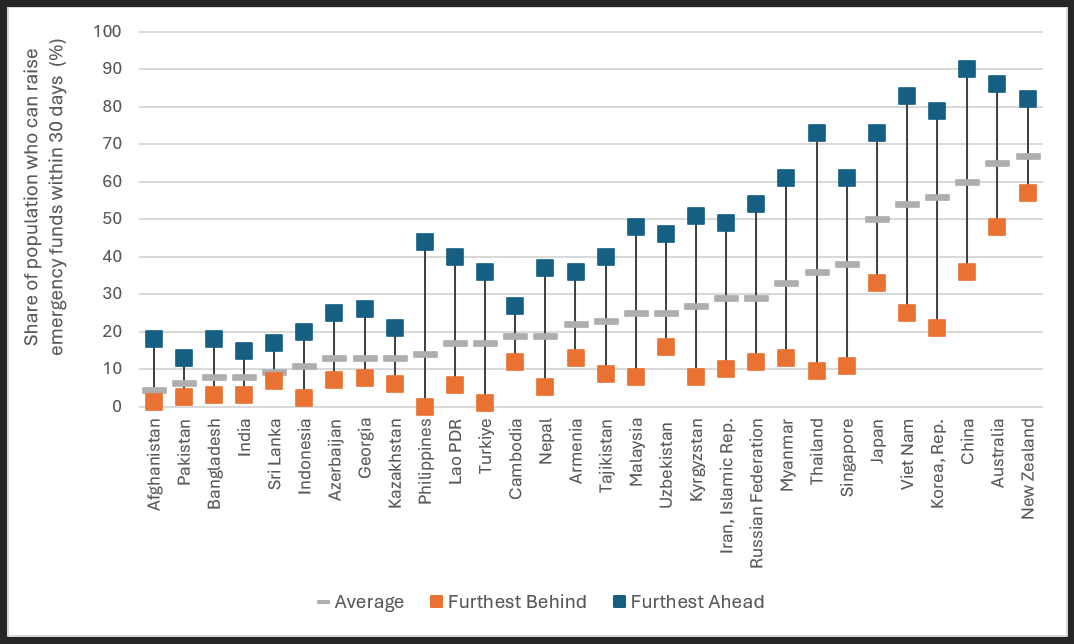

Moving beyond exposure, there are also gaps in coping capacity across the region. More than two-thirds of the population in the region report that it is difficult or very difficult to raise emergency funds within 30 days. This is of concern given that about 45 per cent of the regional population lacks access to any social protection scheme. In low and lower-middle income countries only one in six people can raise emergency funds with smaller gaps between the furthest ahead and the furthest behind groups (Figure 3). Notably, gaps are widest among high income countries. Overall, being poor and having lower education are the key factors that limit the capacity to raise emergency funds. Among poorer and lower educated individuals, women are particularly at risk and left behind.

Figure 3 Gaps in coping capacity across Asia and the Pacific

Note: Author’s elaborations based on ESCAP LNOB algorithm applied to World Bank Global Financial Inclusion Database (2021-2022).

Digital and financial inclusion matter for coping capacity broadly. Information and communications technologies can be effective in reaching affected communities and ensuring their access to critical information including early warning messages. Having access to financial services including bank accounts and insurance enhances resilience to disasters and facilitates recovery from shocks.

Digital and financial inclusion determines the ability to raise emergency funds as well. Across the region, individuals living in rural areas without access to internet are furthest behind in raising emergency funds, as only 8.1 per cent of this group can do so. Men with tertiary education and access to internet are most confident with almost 60 per cent reporting no difficulty in raising emergency funds. Having bank accounts matters too, especially among those with less than tertiary education. In this group people with bank accounts are twice as likely as people without bank accounts to raise emergency funds without difficulty. Poorer individuals with lower education, especially women in some countries, are often excluded from access to financial products and digital technologies.

Role of data analysis and social protection

Leaving no one behind in sustainable development implies that inequalities in exposure, vulnerability and coping capacity towards climate change events are tackled immediately. Universal social protection and active labour market policies play an important role in this regard by building resilience, including among persons in vulnerable situations such as children, women, older persons and persons with disabilities, especially in rural areas. This will also support the implementation of climate change adaptation and mitigation policies. The overall resilience of a country against climate change depends critically on the exposure, vulnerability and coping capacity of its furthest behind groups.

Leveraging data and innovative tools such as the ESCAP LNOB Platform can help identify who and where the furthest behind are within countries. Social protection policies with strategic foresight and when coordinated with environmental policy can help build resilience against both complex shocks like climate change and life cycle contingencies without leaving anyone behind.